“The soul met the id when [Margaret Leighton and Bette Davis] hit the stage. Purity bumped right up against the salty shore that was Bette Davis, and purity won the fight." - Tennessee Williams, 1984

Fifteen minutes into the first episode of Ryan Murphy’s Feud, veteran screen queen Joan Crawford attends a performance of Tennessee Williams’ The Night of the Iguana, co-starring Bette Davis. The mission: sell Davis on starring in the now-seminal What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? despite decades of personal and professional tension between the two. Much is made of the fact that both are in desperate need of a hit movie, that neither cares much for the other as an actress or as a person, that their careers are, to phrase it delicately, in the crapper. But what the show moves too quickly to explain is why, exactly, a rôle in a hit Broadway drama by a foremost playwright could be considered “the skids” by or for Bette Davis.

The short answer: she was in hell and needed out of the play, fast. But delving deeper uncovers a fascinating mass brawl of egos, a Gordian knot of backstage drama that makes the much-mentioned Crawford/Davis saga seem like a Girl Scout Jamboree.

Across countless interviews, (auto)biographies and press clippings it is maintained — largely by the lady herself — that Bette Davis was a classically trained stage actress who got her professional start “trodding the boards.” And this is true. Before decamping for sunny, funny Hollywood in 1931, Davis spent most of 1929 and nearly all of 1930 on the stage playing leading roles. Also true is the fact that she spent the rest of her career acting nearly exclusively before the camera, returning to the living theater only four times for the rest of her life. Each of these four occasions was or ended in disaster, but only one, her penultimate, enjoyed a successful run or involved so many outsized personalities: The Night of the Iguana.

By 1960 Tennessee Williams was America’s premiere dramatist, or at the very least in the same league with the likes of other contemporary giants like Arthur Miller and William Inge. His career would take no small amount of buffeting into the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s, but during the dawn of Camelot any actress worth her proverbial salt would’ve traded her eye teeth for a leading rôle in one of ‘Tenn’s” works. Bette Davis kept hers by stooping to conquer in a supporting part — the blowsy, free-spirited widow, Maxine Faulk.

In 1960 Bette had made only five films in as many years, her most recent Oscar nomination was seven years past and she was fresh out of her fourth and final divorce. A run in one of Tennessee’s Broadway triumphs, while a departure, would seem the thing to invigorate her career, which was her life. Williams had originally wanted her to play prim Hannah Jelkes, a larger part Davis surprisingly refused on the grounds that it bored her stiff. Instead, she set her sights on the role of Maxine. “It wasn't the lead, but it was the best part,” Davis said, though according to producer Charles Bowden she signed under the impression that Maxine’s dialogue and stage time would be bolstered. She would write in her 1962 autobiography, The Lonely Life, “It was certainly the tertiary part, but as I have said many times since, I would rather have the third part in a Tennessee Williams play than a lead in an ordinary play.” Of course, the screen legend would recant this to an interviewer decades later, saying, “I really should have been doing something like [The Glass] Menagerie on the stage, not a supporting role in Iguana or anything. That was my mistake. I thought it would be good for my career.”

In truth, while Williams flattered and fawned over Davis to recruit her, he had his doubts, asking his agent, “Is she physically right for the part, and still more important, does she have the right style for it? If she played it like almost any of her film roles … the effect might be very funny in a very wrong way, and I say this as a great fan of Bette Davis." It’s unanimously agreed upon in print by all involved that it wasn’t exactly Davis’ acting that drew the producers to her: it was her name, which could ensure ticket sales. Katharine Hepburn, another screen legend but one who would enjoy Broadway successes in the course of her career, was asked before Bette to star in the role of Hannah Jelkes. Refusing to sign for more than six months so that she might attend to an ailing Spencer Tracy, instead BD was approached and agreed to a run-of-the-play contract — which would ultimately prove to be shorter than the six months Hepburn had guaranteed. (Tracy would die in the summer of 1967, five years after the play closed.)

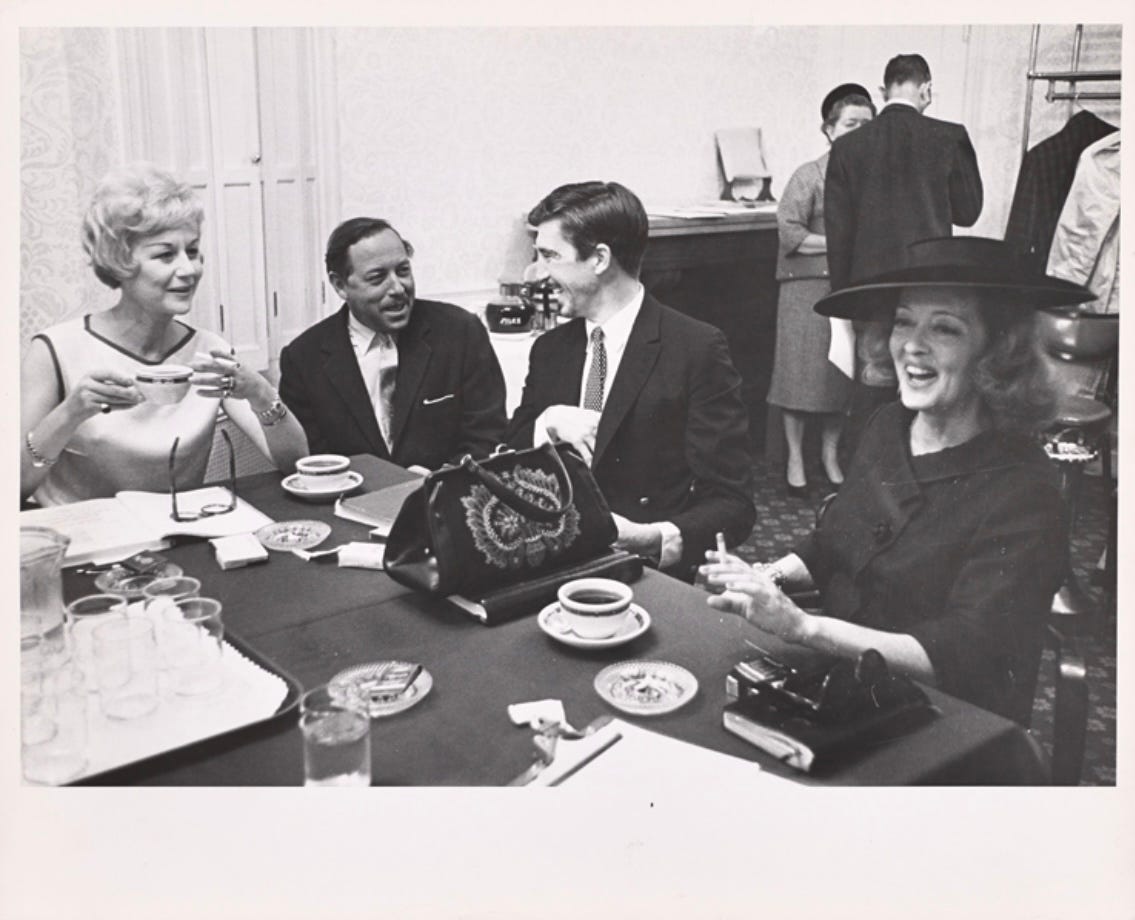

And so on October 9th, 1961, at the historic Algonquin Hotel, the first read-through began for what would be Tennessee Williams’ final Broadway success. “Bette made her appearance in a very royal manner, as befitted such a star,“ writes Williams’ longtime agent Audrey Wood, “and the rehearsal went well,” before adding ominously, “It was merely a lull before a considerable storm.” Stage manager John Maxtone-Graham mentioned in his diary that Davis showed up seven minutes late with her lips “over made-up like a mailbox.”

Though Wood remembered a smooth start, witnesses recall Davis marching up to Margaret Leighton, already a Tony winner for Separate Tables (1957), and barking, “We don’t have to be friends, do we, to work together?” This was considered a declaration of war by the British stage star who got her revenge two days later by going totally, perfectly off-book and leaving the unsteady film legend in her wake. Bette “was frightened to death, you could tell,” recalled director Frank Corsaro, and “looking at [Leighton] in horror, because suddenly this woman was transformed. From that moment on, Davis became a demon." “My cowardice about the theater is astronomical," BD would admit years later to biographer Charlotte Chandler.

In the short period between rehearsals and tryouts — though up until the New York opening Williams kept rewriting and rewriting and rewriting the play — Bette twice announced her departure from the show, at one point screaming at her leading man, newcomer Patrick O’Neal, “I’m sick of this Actors Studio shit!” But she was still very much in the show when tryouts began on a Friday night in Rochester, per Davis’ request at the same theater where she’d made her stage debut more than thirty years earlier. The first show went well, with a few “rough performances” but a generally “receptive audience,” according to Wood. Maxtone-Graham recorded in his diary that “every time Miss Davis made the most pathetic joke, there was roar upon roar of laughter. Giggles and chuckles at her slightest whim. Rather like a very badly or, rather, well-paid canned-laugh audience … When she is on a rampage … she projects rather like the man who calls the states at national conventions.”

At one point during the opening night performance, Davis tripped and fell backstage but instantly righted herself to finish the show and attend the cast party that followed. But the following morning, medics arrived at the hotel and wheeled Davis out to a waiting ambulance; she was incapacitated for both of Saturday’s performances, and when the show headed for Cleveland on Sunday found herself unable to board a train or plane. A private limousine drove her from Rochester to Cleveland, where further trouble awaited. “She was only good on opening night because she was nervous. Then out came the cigarettes and the strut,” Corsaro said. "She was really very disruptive at this point. She never allowed the play to take on any momentum.”

Smoking, strutting Bette rallied for Cleveland but during the four-week engagement in Chicago that followed, tempers reached a new high. The show was savaged by critics but a sell-out thanks to Davis’ name, though the Great Star began skipping performances so frequently that ticket holders were often heard to ask if Miss Davis would actually be appearing that night. To her credit, at each performance she missed, mercurial Bette was diligent about sending an assistant down to the box office to tally exactly how many refunds were requested due to her absence.

Davis or no Davis, the show was running too long and Tennessee, against his will, lopped off a half hour. His reluctance was inspired more by a fear of Bette than any artistic reasons; the only cuts he could find to make all came from the rôle of Maxine. “I can’t,” he pleaded with his producer, director and agent, “I’d be taking [Davis’] part,” which he worried would send her packing. He was half right, for after reading through the revised play Bette called an emergency meeting. With less than a month until the Broadway opening, she demanded — with her signature, “rather hysterical, over-definite pronouncement … usually abysmally ignorant,” in the words of Maxtone-Graham — that leading man Patrick O’Neal be fired. She strenuously objected to his Method acting which entailed minor improvisations that she interpreted as deliberate distractions to throw off her performance.

In her memoirs, O’Neal’s widow writes that “Patrick had no experience with handling a Hollywood-grown ego of that size and probably wasn’t very good at it … [Bette] created nothing but trouble from the get-go … it was outrageous.” By the Chicago run, O’Neal was totally incommunicado with the rest of the cast and crew, holing up in parts unknown to binge drink and avoid his dreaded co-star until showtime. But when word of her edict reached him, O’Neal marched down to the theater to confront her. Slamming through the doors and storming the stage, Bette barked at him derisively, “Where have you been?” Suddenly the young actor lunged at the legend, grabbing her throat with both hands and knocking her to the floor. A group of onlookers rushed to pull him off of her but according to Corsaro, “the thing that was amazing was, as he was doing it, she was smiling.” Pried off of Davis, O’Neal screamed, “You filthy cunt!” before throwing a table and sweeping out of the theater just as suddenly as he’d raged in. “O’Neal wasn’t fired, but the next day, Corsaro was.”

Suddenly made the target of Davis’ ire, she began the unfortunate habit of berating the director between shows, at one point banishing him from the theater and, finally, from the city of Chicago. Initially Corsaro continued to watch the play in secret, taking notes while crouched in the back of the theater, until finally someone in the star’s entourage discovered him and reported back to a livid Bette who screeched, “Go on back to that goddamned Actors Studio!"

Finally, after a painful series of out-of-town performances — “the longest and most appalling tour I’ve ever had with a play,” wrote Williams — The Night of the Iguana arrived at Broadway on December 28th, 1961. The constant rewrites had worked; the show was a hit. Davis’ entrance was met with a thunderous ovation that stopped the show cold and at one point during the deafening applause Bette clasped her hands, raising them above her head like a victorious heavyweight in the ring. Her “grandstanding” had so drained the audience that O’Neal’s entrance was met with indifference, but despite the love of the public, critics made it clear that Margaret Leighton had stolen the show out from under Bette, winning glowing reviews and, later, the 1962 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play.

During her three months on Broadway, the fraught relationships with her co-stars deteriorated to total silence. One night, Audrey Wood went backstage to chat with Leighton, asking if Davis had deigned to speak to the leading lady. Replied Leighton, “Oh, no, dear, not a word, not a word since she returned [from another of her frequent absences]. You know, I believe Bette thinks I should have sent her flowers."

Indignant at being upstaged and by what she felt to be an unsupportive cast, Davis continued to miss performances, eventually making public her intent to leave the play prematurely when on March 14th she told the New York Times’ Louis Calta, "I feel that I have done it long enough for my book …I don't want to go on for another six months. I'm going to rest and walk in the country for about a hundred miles a day." Finally, on April 4th, after 128 performances, Davis walked — deliberately just in time to celebrate her fifty-fourth birthday the next day and to hell with her contract. That night, after giving her final performance as Maxine Faulk, Davis called the cast together to say her goodbyes: “I’m so happy that everyone thinks Maggie is so charming, and Patrick is so brilliant! I’m sorry I had to irritate you so long with my professionalism. You obviously like doing it your way much better. Well! Now you can!”

Five weeks to the day after that heartwarming speech, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford signed their contracts to appear in Baby Jane?

During what she made sure all and sundry knew was her last week in the show, the producers brought another film star to see and hopefully take over the part: Shelley Winters. Exactly one year before Bette’s last performance Winters had been awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress (her first of two), was like Davis a celebrity draw, but came with her own thorny professional reputation as, in the words of one reporter, “excitable, moody, bombastic, possessive, self-conscious, emotional, defensive, sarcastic, [and] impatient.” Williams would write to a friend, “It’s hard to say which was worse but at least La Davis drew cash and La Winters seems only to sell the upper gallery.”

In her second of two autobiographies Winters remembers seeing Bette as Maxine and being baffled:

“There was something very strange about the performances. Bette Davis seemed to be shooting her lines right at the audience, facing squarely front and not talking to Margaret or Patrick at all. She was getting uproarious laughs but I knew she wasn’t that kind of actress. What the hell was going on? … Did Bette Davis and Margaret Leighton hate each other so much that they couldn’t act together?”

Still, despite a “gut feeling” regarding Davis’ known unhappiness in the play and her mysterious, shockingly unprofessional departure, Winters accepted, taking over for understudy Madeleine Sherwood after less than a week. Before assuming the rôle, Winters saw the show once more after Davis’ departure, watching Sherwood in the part. A staple of Williams’ adaptations on the stage and screen, the stage actress wasn’t enough of a name to stop hordes of stunned theatergoers — Davis’ exit went unannounced so as not to cause a flood of refunds — from storming the box office to get their money back. Winters curbed this problem but immediately faced the same trouble that had plagued Bette. Writes Shelley:

“The first time I walked into my dressing room backstage at the Royale, written on the mirror in very red lipstick were the following words: ‘SHELLEY — AFTER YOUR FIRST OR POSSIBLY SECOND PERFORMANCE YOU WILL FIND OUT WHY I LEFT THIS SHOW. BETTE DAVIS.’ Knowing how up-front Bette Davis was, I began to tremble with fear as I gazed at this message. What could she mean? … I soon found out.”

Consummate professional Sherwood remained in the rôle of understudy but, Winters noted, avoided the Royale Theater like the plague, phoning in her location before curtain every night without ever bothering to actually show up. Her leaving Davis’ cryptic lipstick message to Shelley up on the mirror led Winters to believe that whatever had chased Bette Davis out of the play had also happened to Sherwood, and she would soon be proven right.

Despite a successful first matinee with a responsive audience that cheered Winters, the “second performance was dismal.” SW’s third and fourth shows were just as tepidly received, and she couldn’t understand why until one of the young men in the cast came backstage to tell Winters to “pay attention to what's happening on the other side of the stage while you're so deep in your Method stuff." What was happening was something that, to hear Winters tell it, vindicates Davis’ fury:

“Margaret Leighton or Patrick O'Neal would say the setup of my joke and then move slightly for a few seconds, keeping the eye of the audience so the audience was not looking at me or even listening. So when I gave the punchline they barely heard it. It's hard to believe but that is what these two brilliant professional actors were doing. It took me about three performances to make sure. And then I understood why Miss Leighton had gotten such fabulous reviews and the great actress Miss Bette Davis had gotten some very good but many so-so ones … It's a wicked British stage trick and I have never seen it in an American production. Either Leighton, may she rest in peace, was so competitive with Davis or she was so insecure that she wanted the audience to only remember her. She obviously had taught Patrick O'Neal to do it too; as soon as I started to get the attention of the audience she and Pat resorted to these stage tricks. The only way I could combat it was by delivering my lines straight and loud at the audience as soon as the setup of the joke was uttered. I stood this kind of acting for nine months. I would be damned if they would run me out of the show and close Tennessee's play.”

One night Winters could no longer stand the rampant unprofessionalism and shoved her prop bar cart across the stage, where it toppled O’Neal who took Leighton down to the floor with him. “I went on with my monologue,” Winters recalled, “and felt very proud of myself.”

Though she’d signed on to play until January 1963, Winters chugged along until September 1st, 1962, recalling her record five-month run as “a blur,” though the blurriness might be attributed to her habit of sneaking off between her scenes — the character of Maxine is offstage as much as she is on — in full costume and makeup to chin and gin with the fellas in the bar across the street, much to the consternation of the rest of the show. “Miss Winters has had differences with other members of the cast as well of the management,” reported one paper in late August. “It has been no Broadway secret that she had threatened to quit on previous occasions.” With Shelley went her star power and, consequently, the show. Priscilla Morrill, the new understudy for the rôle of the Widow Faulk, took over for a few weeks until the show closed on September 29th, after 316 performances.

And after all this infighting, sabotage and physical violence, when the film version was announced the following year, none of the stage actors reprised their rôle on the big screen. Richard Burton got Patrick O’Neal’s, Deborah Kerr Margaret Leighton’s and Ava Gardner Bette Davis’/Shelley Winters’. “I was never asked," Bette told one biographer. “At the time, I said publicly that Miss Ava Gardner was too young for the part, but I knew the truth. I was too old.” Twenty years after that, Davis would sum up the entire experience in a phone interview with James Grissom:

“I was not treated well by the producers of Iguana … The director was without force or talent. And don't get me started on my co-stars! But let me tell you: When you are a good actress, and a star, and you leave a production that was shabby to you, there is no greater revenge than in having your role taken on by Shelley Winters. I could have never imagined a worse punishment for that production than Shelley Winters. I won that battle.”

Williams, in an interview with Grissom from around the same time, remembered it a little differently:

“She was indomitable; she was impossible; she was fabulous … She was out of her element on Iguana. If she had ever truly had a command of her talent on the stage, she had lost it by that time … Of course this made her terribly angry, so most of what we saw was the virago, railing about the set and the costumes and the audiences. She both wanted for them to love her and want to see her, but would then chastise them for being stupid fans who weren't there to appreciate my play … She could never bring herself to ask for anything — she loved to demand, to rail. I wanted her to be great, but she was not: She was Bette Davis, slumming in a play. To my amazement she would look out over the audience, counting the house, making no attempt to be in character unless she was speaking. I was, shall we say, disappointed … I continue to enjoy Miss Davis through her films, and through those other great performances she gives in interviews, during which she gives the impression — false, in my opinion — of a smart, decent, upright lady. Better, in so many circumstances, to not meet people you admire.”

Sources:

The Oxford Book of Theatrical Anecdotes by Gyles Brandreth

The Girl Who Walked Home Alone by Charlotte Chandler

Bette and Joan: The Divine Feud by Shaun Considine

The Lonely Life by Bette Davis

The Dramatic World of Tennessee Williams by Francis Donahue

Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh by John Lahr

Talk Softly: A Memoir by Cynthia O’Neal

Mother Goddam: The Story of the Career of Bette Davis by Whitney Stine

Shelley II: The Middle of My Century by Shelley Winters

Represented by Audrey Wood

“Bette Davis Has Laryngitis,” New York Times, Mar. 4, 1962

“Miss Davis Quits ‘Night of Iguana” by Louis Calta, New York Times, Mar. 14, 1962.

“Shelley Winters Quitting ‘Iguana,” The Berkshire Eagle, Aug. 28, 1962

“Former agent tattles on boozing, troublesome, high-and-mighty stars” by Kitty MacNab, World Weekly News, Dec. 22, 1981

Tennessee Williams interview with James Grissom, 1980s

Bette Davis interview with James Grissom, 1980s

This was totally engrossing. Still a little confused about the onstage "movement trick." How they pulled it off, what it looked like... Hard to know whose side to be on hahaha

Wow, an incredible read!!